From disruption to innovation: Bridging a growing cultural gap

If we want real innovation, we need to stop looking for ways to circumvent the federal acquisition system and work together to improve it, writes Stan Soloway.

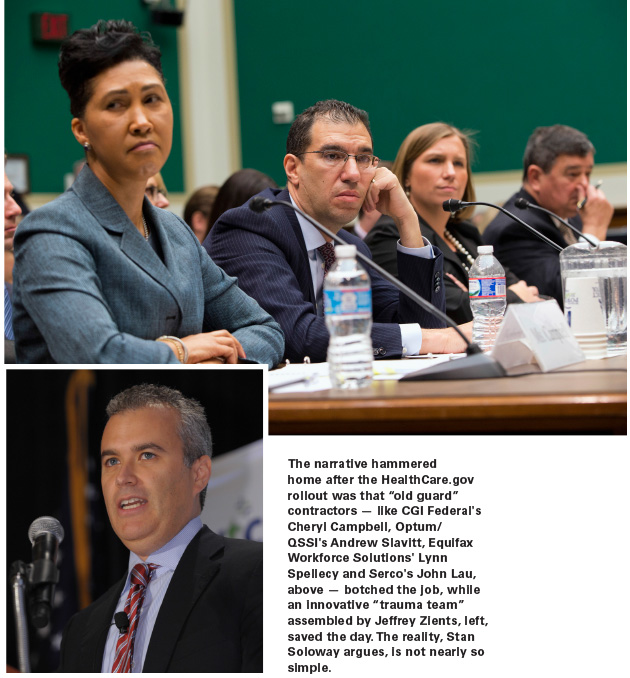

Reading Steven Brill's March 10 Time magazine cover story on the "rescue" of HealthCare.gov, one could not help but be struck by two key elements. First, the team of uber-talented technologists who led the repair process did so at significant personal sacrifice, working for free while on leave from what were, in many cases, high-paying jobs. Second, the clear assumption was that the "traditional" government contractor community could not have achieved what the so-called trauma team did.

The first point is demonstrably true. The second, however, is far too facile. After all, some of those "traditional" contractors were quite successful on a number of individual state health insurance exchange initiatives. Even CGI Federal -- the company most often vilified as "failing" on HealthCare.gov -- achieved great success on Recovery.gov, the highly visible initiative that supported the economic stimulus program. And many of the actual "fixes" to the HealthCare.gov system were made by the very individuals who were involved in the original, troubled launch.

In other words, the problems identified in the HealthCare.gov fiasco are more complex and nuanced than some would lead us to believe.

To better understand those problems and the ways in which they can be overcome, one needs to take a closer look at what was common to the successes and the failures, and vice versa. Although the quality and capabilities of all involved in the process remain crucial, of equal if not greater primacy were clearly defined requirements, process discipline, management capacity and other factors largely unrelated to who was doing the work.

Technical skills are essential, but driving success in complex circumstances also requires deep environmental awareness and strong management and leadership. Members of the trauma team clearly brought critical levels of the latter, but without experience and environmental awareness, they, too, would likely have failed.

Nonetheless, a lack of experience and awareness is becoming increasingly common across government. And it is creating a troubling disconnect that threatens to undermine the government's performance and its credibility with taxpayers.

The keys to sustainable change

That disconnect is not unique to government. Indeed, it formed the core of Yiren Lu's thoughtful March 16 New York Times Magazine story "Silicon Valley's Youth Problem." Lu is a 28-year-old graduate student in computer science at Columbia University who has spent considerable time in Silicon Valley. Her perception is that her peers are motivated by the chance to disrupt existing paradigms and practices, and top coders and developers do so with uncommon creativity and brilliance.

But Lu also observes that most of the major technological advances still emanate from "old guard" companies, including Apple, Cisco and IBM, which her peers tend to view with varying degrees of disdain and for which few of them want to work. Thus, the "youth problem" she describes is a study in irony: a community that is extraordinarily adept at finding new and exciting applications for technologies that are, in large part, made possible by the very entities its members tend to hold in low regard.

But it is more than irony at the heart of Lu's article. She reminds us that in technology as elsewhere, there are critical bridges that are central to innovation and that real innovation typically results from a combination of forces. It requires technology, highly creative applications of that technology, and a depth of systemic understanding and awareness that provides the requisite insight for scaling the first two elements to make a meaningful difference. It is often the latter element that ultimately determines whether a project succeeds or fails.

As Tom Agan, founder of innovation and brand consulting firm Rivia, reported in 2013, research has shown that the average age of the most impactful innovators is much higher than most people realize. Although the impetus for change and the most creative thinking often come from younger, less constrained minds, the ability to implement and scale in ways that drive sustainable change requires time and experience. After all, how can you disrupt and create sustainable change if you don't know what's there and how to navigate around it? Thus, it should come as no surprise that the most impactful innovators are far more likely to be individuals like Steve Jobs, Elon Musk and Nick Woodman than Mark Zuckerberg.

This brings us back to the Time article and to the role of the disconnect in government. Recognizing the value of disruptive capabilities, the government is experimenting with a variety of ways to access and capitalize on them: procurement contests, crowdsourcing, NASA's International Space Apps Challenge, the U.S. Agency for International Development's Global Development Lab, and the innovation funds now resident in agencies such as the departments of Education, Homeland Security, and Health and Human Services.

Each of those initiatives seeks to identify and access creative, scalable ideas. Each also recognizes the sometimes-restrictive nature of the federal acquisition process and is based on a desire to open the government's aperture.

Yet each also recognizes the importance of competition and is conducted in a manner that is open to all relevant, qualified parties, including current participants and new entrants into the government marketplace. The projects' leaders don't presume that any one segment or community has all the answers. Instead, the initiatives represent healthy and constructive efforts to tap the "community commons" for fresh ideas and thinking.

New guard needs the old guard

But some of those efforts, at least as currently constructed or articulated, are more illustrative of the disconnect described earlier.

For example, the State Department has a little-known effort to directly link embassies and consulates with tech startups that have capabilities relevant to their needs. Loosely tied to the Obama administration's Startup America program, which sought to facilitate connections between tech startups and Fortune 500 companies, this brainchild of tech entrepreneur Rebecca Taylor sounds, at least at first blush, like a great idea. But there's a fundamental problem with the concept. It presumes that only tech startups -- indeed, only those aware of and connected to this closed marketplace -- have ideas that might help embassies and consulates. It effectively picks winners and losers in advance and creates a closed system at the very time the focus should be on expanding and improving the broader marketplace. In that sense it also runs directly counter to the market-focused premise of Startup America.

Although no data is apparently available to assess the relative success of the initiative, the inherent presumption is that current, "traditional" companies -- the old guard -- have nothing to offer. In addition, as Taylor herself has articulated, it is intentionally designed to get around the barriers created by the federal acquisition system.

Similarly, based on the same presumption, the General Services Administration's new 18F project describes itself as a government startup that will directly deliver to federal agencies digital solutions that "tackle the toughest problems in government." Building on the success of the Presidential Innovation Fellows program, 18F will hire 50 to 200 "world-class coders" to work at GSA's headquarters in Washington, at its offices in San Francisco and perhaps elsewhere.

Here, too, this sounds like a great idea; who could be opposed to putting some of the best and brightest to work on behalf of the government? But whether 18F can drive real innovation as opposed to isolated, incremental improvement remains a significant question.

After all, 18F is self-contained and intentionally constructed outside the federal acquisition system, and absent any competitive pressures. In fact, 18F's goal is to deliver, on a sole-source basis, direct service to its agency customers.

Make no mistake about it: The federal acquisition system is often calcified and inefficient, and it is in need of significant improvement. Hence, frustration with it runs high. But rather than improve the system to facilitate new ways of doing business and drive real change, 18F is designed to skirt the system altogether.

In the end, although a handful of 18F customers might benefit from the occasional creative application or new digital capability, it is hard to see how the program will lead to real, sustainable innovation.

After all, the mere presence of disruption, which 18F's approach represents, does not automatically lead to innovation. As noted earlier, real innovation requires more than a disruptive idea or application. Innovation comes when that disruptive idea or capability can be scaled in a way that is replicable and leads to fundamental change in how work is performed to generate improved and less expensive outcomes. As currently constructed, 18F is much less about scaling innovation than it is about delivery.

Keeping the door open

18F could also have a negative impact on a wide range of companies that have creative ideas and talent but are required to operate within the confines of the very system 18F is able to circumvent. The rigidity of the current system often stymies the efforts of both new and long-standing contractors to bring innovative solutions to government. But who is to say that, given the same flexibilities and freedoms afforded 18F, any of those sources couldn't provide equal or even better results? And how would an 18F fare under the same policies and processes to which others must adhere?

18F has the potential for real impact and value, but to fulfill that potential requires that the program amend its concept of operations to clarify that as it delivers solutions it will also map all the points along the way that create barriers to success under the normal system. Those lessons should form the basis of aggressive efforts that GSA could help lead to fundamentally improve the system so that it becomes the truly open, innovative, healthily competitive marketplace we all want it to be. That, more than direct delivery of services, would be consistent with GSA's mission and objective of becoming the government's premier acquisition organization. And it could lead to real innovation.

Finally, 18F and the State Department's program ignore vital lessons like those reported by Rivia's Agan. Experience, customer knowledge and insight are essential to driving real change and innovation. Those traits are common to virtually all the most successful innovators. Given the complex and arcane processes under which government operates, which are not limited to acquisition, that knowledge forms a crucial bridge between forward-looking, experienced firms and new entrants that bring creative and disruptive capabilities. Although most of the other innovation initiatives leave the door open to or embrace that reality, 18F and the State Department's program, as currently constructed, turn their backs on it.

The extraordinary possibilities presented by the pace and scope of technology change will likely only work to the government's and taxpayer's advantage if the people creating disruptive capacities either have extensive working knowledge of navigating the government maze and customer mission needs or can partner with others who have that knowledge and experience. The combination of the lessons learned through 18F and the recognition of the value of such bridges could be enormously powerful tools in the creation of a healthy, competitive marketplace that encourages and supports such linkages.

That marketplace could form a significant catalyst for the kind of change the acquisition system so badly needs, particularly as we think about the future of acquisition. To do less could mean settling for minor, isolated improvements at the expense of real innovation and change.

If we want real innovation and a government that has access to the full array of capabilities that create both disruption and sustainable change, then we need to overcome this divide and work together to improve the system. Assuming that one sector or another can go it alone is naïve. Instead, our collective objective should be to create a modern, competitive marketplace that doesn't presume winners or losers and doesn't assume outcomes. Instead, the proof will be in the performance, regardless of the performer.

Some old-guard players might not succeed in that space while others will perform magnificently. And given the high failure rate of tech startups, the same will be true for the new guard. But who is the government to decide the winners in advance? Why would it even want to?