Contractors who tell don't have same protections as feds

Though the number of federal contractors has grown significantly over the past decade, examples of whistleblowing contractors are extraordinarily rare, and they don't enjoy the same protections as federal employees.

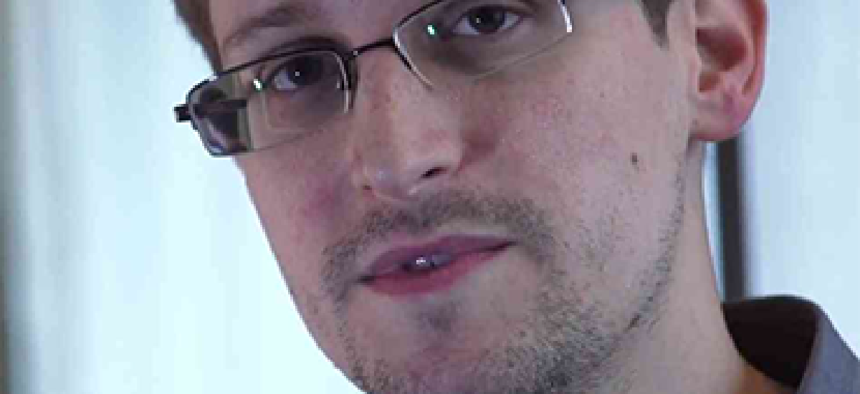

As a contractor, Edward Snowden would not have been eligible for whistleblower protection under federal law.

Would Edward Snowden, the National Security Agency contractor who publicly disclosed details about the agency's far-reaching surveillance efforts in June, really have had whistleblower protection under federal law had he used internal channels to disclose the information?

President Barack Obama and his administration have repeatedly made that claim, most recently at a news conference on Aug. 9, when Obama said his October 2012 presidential policy directive (PPD-19) provided whistleblower protection for members of the intelligence community.

"Other avenues were available for somebody whose conscience was stirred and thought that they need to question government actions," Obama said.

A report from the Washington Post questions Obama's claim on the basis that PPD-19 covers only federal employees, not government contractors. In addition, while the policy directive was announced Oct. 10, 2012, it was not to be implemented for 270 days, or by mid-July 2013.

Obama "badly misled the American people," Stephen M. Kohn, executive director of the National Whistleblowers Center, told the Post, adding that "none of the procedures were effective at the time" Snowden made classified disclosures to The Guardian and Washington Post.

"They are a workforce of people with whom we entrust our nation's deepest secrets, but give them no protections if they want to disclose wrongdoing," Danielle Brian, executive director of the Project on Government Oversight, also told the Post.

The White House didn't say whether Obama's policy directive was implemented, but contended contractors – while not mentioned in its language – do have whistleblower protections.

"The bottom line is that Mr. Snowden could have lawfully raised his concerns without making unauthorized disclosures," White House spokesman Eric Schultz told the Post.

Snowden, a previous employee of the Central Intelligence Agency, was employed by Booz Allen Hamilton when he disclosed classified information.

Though the number of federal contractors has grown significantly over the past decade, examples of whistleblowing contractors are extraordinarily rare.

A 2012 report by the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) found only one defense contractor was substantiated as a whistleblower by the Department of Defense Inspector General out of 2,409 cases.

That ratio is unlikely to encourage other contractors to come forward to report wrongdoing.

Even if Snowden had been a fed, it's unclear whether whistleblower protection would have applied to him.

For one thing, it's arguable whether he disclosed information that would make him a whistleblower under existing law.

The Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 prohibits reprisals against federal employees who report waste, fraud, mismanagement, abuse or illegal activity. However, national security matters do not fall under those protections, according to John Palguta, vice president for policy at the Partnership for Public Service.

Palguta worked for 20 years at the Merit Systems Protection Board, an agency created through the Civil Service Reform Act to adjudicate federal employee appeals. Feds tend to win about 20 percent of whistleblower cases brought before the MSPB. Snowden, now charged with three felonies and hiding in Russia, would not have even gotten that far.

"There is a good argument that what [Snowden] put out there certainly had an impact on national defense," Palguta told FCW.