Taking video analytics to the next level

The technology has become more common in the federal space and even in consumer settings, but it still has a long way to go.

The science of pulling useful data out of digitized video -- or video analytics -- is an increasingly confounding task given the staggering amount of archived video and new footage captured every day from an expanding array of devices. It's not just coming from fixed and pan-tilt-zoom cameras any more: Lapel cameras, helmet-mounted cameras, consumer technologies such as Google Glass and the ubiquitous smartphone all contribute to the video stream.

Government uses tend to focus on areas such as perimeter security, where motion detection and object tracking are important applications of video analytics by agencies such as U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which started using the technology in the early 2000s. Government agencies also use video analytics to capture images of license plates and identify people.

Although the current applications have proven useful, today's technology has significant limitations. Government, academic and industry researchers confront a number of challenges that range from exploring ways to more efficiently comb through huge stores of video -- essentially a big-data problem -- to coping with cameras that move around as they record objects that are also in motion.

Furthermore, developments in software have failed to keep pace with the explosion in video camera hardware. Jie Yang, a program director at the National Science Foundation, said the field of computer vision, a key component of video analytics, has made progress in terms of object detection and tracking, facial detection, and license-plate recognition. But high-level video analysis, which would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the objects recorded in video and their relationships to one another, is far from mature.

"People are working hard, but we are not really there yet," said Yang, who is responsible for the Information and Intelligent Systems core programs and the National Robotics Initiative at NSF.

Why it matters

Video analytics tools are often associated with security. The technology can continuously monitor multiple video feeds for movement or other details that could escape the attention of a human observer. Agencies that protect government-owned buildings and infrastructure use the technology to get more out of their investments in video surveillance.

"We are seeing more agencies putting out more cameras," said Warren Brown, president of ObjectVideo, which licenses its video analytics technologies to IP video manufacturers. "Inevitably, there are not enough people to watch all of that video, and that is where the...push for analytics comes from."

Law enforcement agencies, meanwhile, increasingly rely on video analytics for facial recognition. The technology played a role in the investigation into the Boston Marathon bombing last year, and some federal agencies continue to explore that use of the technology. The FBI, for instance, has launched a study of video and digital image processing and analytics, issuing a request for information last year asking industry leaders to demonstrate capabilities in facial, vehicle and license-plate recognition.

In the RFI, officials said they would like to "identify current capabilities, assess gaps and develop a road map for the FBI's future video analytics architecture."

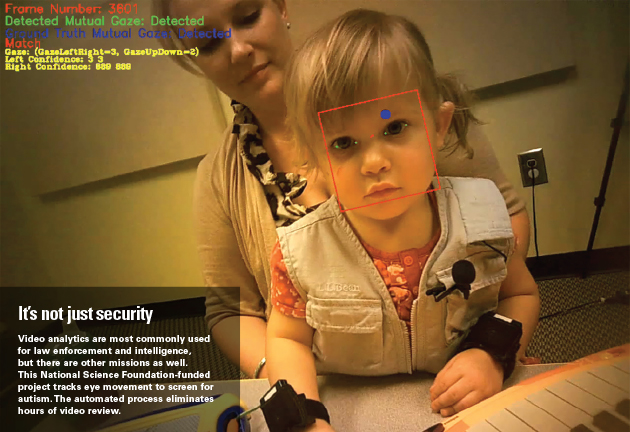

The technology, however, reaches beyond the realms of security and law enforcement. Yang cited the example of a research project at the Georgia Institute of Technology that uses video analytics to help screen children for autism. The research is funded by a $10 million grant from NSF's Expeditions in Computing program.

Georgia Tech's initiative involves using facial recognition and video analytics to detect anomalies in a child's eye contact with adults that could indicate autism. The automated approach eliminates hours of studying video frames to identify moments of eye contact, researchers said.

Video analytics technology is also finding a niche in humanities research. The Large-Scale Video Analytics (LSVA) research effort uses supercomputing power to explore video collections. The project brings together researchers from the University of Southern California (USC); the Institute for Computing in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences; and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, which is supported by grants from NSF and other federal agencies.

Virginia Kuhn, an associate professor in USC's School of Cinematic Arts, said it is hard to imagine an area in humanities research that would not benefit from improved video analytics.

"There [are] the 115 years of cinema [and] the massive amount of broadcast television and cable shows that are migrating to sites like Netflix, Amazon [Instant] Video and Hulu," she said. "All of these are important aspects of culture insofar as they impact our sense of identity and our knowledge of the world."

The fundamentals

Video analytics software that zeros in on the object or event of interest is part of a broader architecture that includes cameras, encoders, servers, storage and networks. The analytics capability might reside on servers, the cameras or the encoders, which convert video from analog cameras so the moving images can travel over IP networks.

Moving analytics to the edge -- on cameras or video encoders -- provides several advantages, according to Scott Dunn, director of business development at Axis Communications, a network video vendor.

"First, the camera can process all the video before it's sent over the network," he said. "So, for example, instead of streaming constant video to read license plates, the camera knows to send only the relevant five-second clip and process the plate number. This also means the video being analyzed is raw and uncompressed, as opposed to server-based intelligence that uses compressed video. The end result of edge processing is that video no longer must be sent to the centralized server, meaning you can dramatically decrease bandwidth and centralized computing power needs, increasing savings for the total system."

Indeed, storage is an important, if unsung, component of the architecture. In smaller-scale environments, videos might be housed on digital or network video recorders. Organizations that need the scalability to support vast amounts of video can invest in network-attached storage or storage-area networks.

The demand for such storage is growing rapidly. In February, MarketsandMarkets estimated that the global market for video surveillance storage will grow from $4.9 billion in 2013 to $10.4 billion in 2018, a compound annual growth rate of 16.3 percent.

Furthermore, the report notes that the prices for hard disk drives are going down. Consequently, the declining cost of storage could encourage the growth of the video analytics solutions that rely on them.

Camera prices are also dropping. Brown said thermal imaging cameras, which once cost tens of thousands of dollars, have declined sharply in the past 18 to 24 months, with the price range for some devices dipping to $1,000 to $2,000.

Brown said the lower prices make thermal imaging a more cost-effective option relative to other perimeter-protection tools, and those cameras can be enhanced by using video analytics.

The hurdles

The volume of available video -- and the time it takes to ingest and process it -- is an important limitation. "Working with a large number of images is a big-data problem," Yang said. "The majority of the images, we can't touch them."

"It's...time-consuming but also nowhere near an exact science," Kuhn said.

The sheer amount of video complicates activities such as content tagging to facilitate searching. "Tagging is too labor-intensive for humans to do, and there are also problems with tags since a word can never adequately represent an image," Kuhn said.

The LSVA project seeks to harness the power of high-performance computing -- specifically the Gordon supercomputer at the San Diego Supercomputer Center. Gordon can analyze large video archives, but human experts supplement its work. For instance, when the computer searches a video archive, researchers verify the results.

Another ongoing challenge involves recognizing and matching objects recorded on video. Even facial recognition, which is considered fairly mature, still stumbles on occasion. For instance, recognition systems mainly focus on the front view of faces, but many of the faces recorded in surveillance video are in profile because people tend not to stare directly at wall- or ceiling-mounted cameras.

"The side of the face is much harder" to match, Yang said, noting that the profile recognition issue has yet to be fully resolved.

Matching also proves difficult in the case of transformable objects, said Gregory Pepus, managing partner and founder of Flex Analytics. Cars and buildings, for example, typically don't change shape, but that's not the case for people and animals. A person can stand upright or contort into a yoga position.

Flex Analytics taps technology from companies such as piXlogic to address that problem. Pepus said that with PiXlogic, "we are very far along" in solving the issue of matching transformed images. The piXlogic technology segments video into smaller pieces to identify more and more granularity, he added.

Analyzing video generated by mobile cameras is another challenge. Brown said most algorithms assume that the camera isn't moving, so video analytics providers must start from scratch on new algorithms.

Mobile cameras of all kinds, including those integrated into unmanned aircraft systems, are becoming an important new source of video, and Yang was optimistic about the evolution of video general. "It creates a lot of new challenges and opportunities," he said.