New study could help bio-threat response

The goal is to be able to predict outcomes from terrorist incidents involving anthrax.

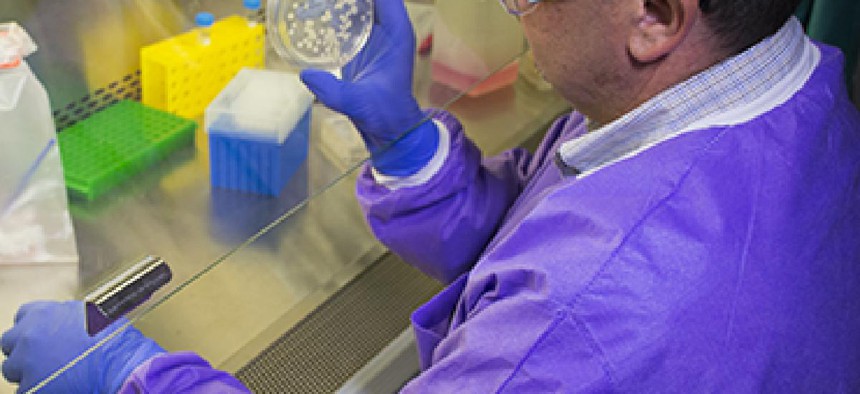

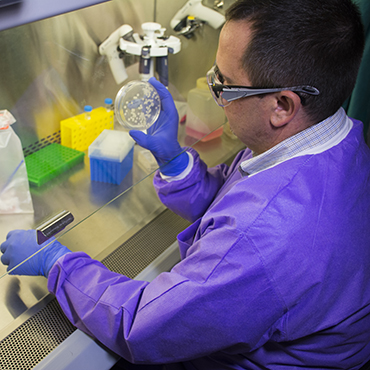

PNNL microbiologist Josh Powell looks at anthrax spores, which have developed into bacteria over the course of 12 hours. (Courtesy of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory / Flickr)

The latest research on anthrax will inject a new class of human-based data into the National Biological Threat Risk Assessment data tool developed and used by the Department of Homeland Security.

Research backed by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and DHS's Science & Technology Directorate cultured human lung cells that have been infected with a benign version of anthrax spores to yield new data on how anthrax grows and spreads in humans.

The study, published in the Journal of Applied Microbiology, will help provide credible data for human health related to anthrax exposure and help officials better understand risks related to a potential anthrax attack.

Previously, only data on infected rabbits had been available, according to a PNNL statement. That data had been extrapolated to cover human exposure to the bacteria, with sometimes uneven results.

"What we're learning will help inform the National Biological Threat Risk Assessment — a computer tool being developed by the Department of Homeland Security," Tim Straub, a PNNL chemical and biological scientist, said in the statement. "There is little data to estimate or predict the average number of spores needed to infect someone. By better understanding exposure thresholds, the ultimate goal is to be able to predict outcomes from terrorist incidents involving Bacillus anthracis."

PNNL said it is too early in the process to say what the new data means for humans, but the study's methods and results might resolve a long-standing debate on how anthrax spores germinate in the lungs before making their way to the bloodstream -- a point of contention in the research community, with some speculating that spores must first enter the blood stream and then grow into bacteria that can cause damage and death.

Researchers hope to reproduce the study using a more virulent strain at DHS's National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center in Frederick, Md., rather than a similar but milder strain used in the study, which is virtually unable to cause illness in people or animals.

In the next phase of the project, PNNL said researchers will put the experimental data into a computational model to more accurately predict outcomes of anthrax exposure. According to the lab, a model based on primary cell data could calculate how much time doctors have to initiate treatment, how many spores are likely needed to cause disease or mortality in humans, or be able to determine if there is a "safe" level for exposure or a required level of cleanup of a contaminated area.

Once the models are refined with data from the latest experiments, the numbers will be checked against animal data to see if they are predicting outcomes accurately. The models could also potentially speed future drug design.

Researchers also hope the fundamental findings and models can be applied to other diseases related to inhaled pathogens, such as the flu or SARS coronavirus.