Innovation in government can come from anywhere

Steve Kelman sees potential in a public-domain piano experiment.

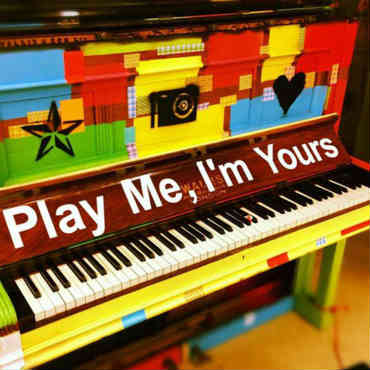

France's public-domain pianos project was inspired by the Play Me I'm Yours organization's efforts.

I am guessing that few people would identify a railroad system, particularly one run by the government, as a hotbed of innovation. In France, strong railway unions might make the idea of innovation in such a setting even less plausible.

So I was surprised and delighted to read a story recently in the New York Times entitled, "Miss a train in France, maybe catch a tune." It was about the installation, in the central halls of some 100 train stations in France, of a piano available for playing -- not "by a paid musician, or even a street entertainer busking for coins," but by "a random passer-by, jamming for the fun of it." Basically, anybody can start playing whenever a piano is unused. "The pianos," the article notes, "have proved to be very popular, and the music, blending with the sounds of shouting passengers, screeching trains and rolling suitcases, can give French stations a peculiar soundscape."

As I read this story, I thought about it as an example of an innovation that improves the quality of life, coming from an unexpected source. If the French railroad system can roll out a cool innovation such as this one, any organization can -- including your own.

I contacted the author of the story, a Times reporter named Aurilien Breeden, to try to learn more about where this innovation came from and how it happened. He kindly replied and provided me with more background.

It turns out the innovation was inspired by a British organization called Play Me I'm Yours, founded in 2008 by an artist named Luke Jerram. The group organizes shorter-term events in cities around the world, usually two weeks or so, where it cooperates with local partners to deliver donated pianos and accompanying artwork to public locations. The French railroad locations are run by the national railroad company, with the pianos rented from Yahama, and placed on site permanently.

The innovation was introduced in the French railways at Paris' Montparnasse station in 2012, following temporary events organized with Play Me I'm Yours. According to Breeden, it was a local initiative from the Montparnasse station, and did not need approval from headquarters. Then in 2014, the unit within the national railway company in charge of running stations throughout France, Gares & Connexions, decided to expand this to about 100 stations.

To sum up: The idea came from outside, not inside, the organization, but somebody inside picked it up. They started very small (one station, no higher-level approvals). Then the organization decided to try this at a few other places and, when it worked, to expand it further.

Notably, the article quoted a Gares & Connexions official declaring that "none of the instruments have been vandalized to this day, or even merely damaged." Sometimes, we worry too much in government about possible downsides without asking how much of a risk they truly are, and wind up losing an opportunity to achieve a change's benefits.

My message from this to folks working in government: If you think your organization can't innovate, think harder.

If you look around you, scan your environment, and use your brain, you are all but sure to come up with ideas about an innovation that can make things better and that can be tried out even in a stodgy government environment. Most of these ideas, like the pianos in railway stations, are micro-innovations, changing an organization one experiment at a time, rather than through a big bang. There's a real advantage to that, because it democratizes innovation and makes every civil servant a potential innovator in his or her workplace.

My message to government managers and executives: Make micro-innovation a project in your organization. Talk about how micro-innovations can come from anyone. Talk up examples of micro-innovations in your organization, in speeches, newsletters and so forth. Some might want to make a contest or awards occasion around this, but I'm inclined to think the spirit of this emerges best if recognized more informally rather than through some official award.

If we can get enough micro-innovations, they will add up to something bigger -- better government.