What 9/11 looked like inside the federal IT community

Mark Forman, the former administrator of the Office of E-Government and widely considered the first federal CIO, shares his recollections of the attacks of September 11, 2001.

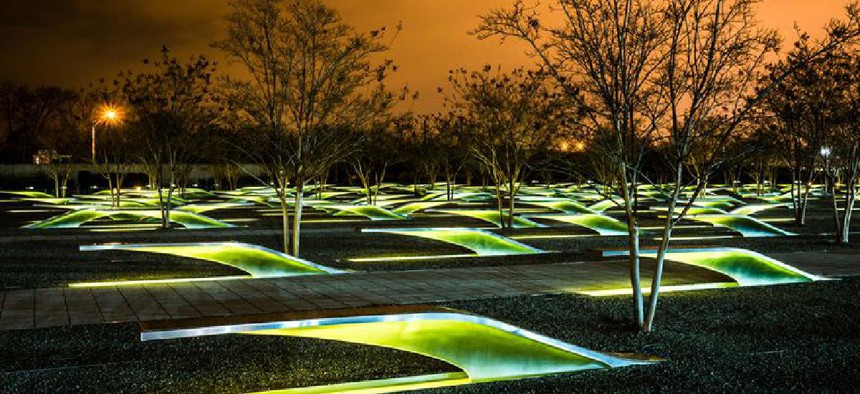

The National 9/11 Pentagon Memorial. (Editorial credit: stock_photo_world / Shutterstock.com)

Mark Forman was serving as administrator of the Office of E-Government at the Office of Management and Budget – the federal CIO post -- when the attacks of September 11, 2001 took place. He's had senior roles in the private sector at Unisys, SAIC and other firms. Currently, Forman is executive vice president at Dynamic Integrated Services

FCW: Where were you when you heard about the attack?

FORMAN: I'd been in the job almost almost exactly three months. At that point we were finishing up the e-government strategy, literally that day. And that morning, I was briefing the annual HR directors conference, which was at University of Maryland. I was on the stage talking about the whole e-government strategy and what the President's Management Agenda for e-government was about and how it would affect them. And I was interrupted by the fact that there had been a plane that crashed into the World Trade Center. So they took down my charts from the screen behind me and put up the CNN feed.

And it was exactly at that time when the second plane flew into the other tower, and so were all shocked. And of course, then they said that there was apparently a bomb that had gone off in Pentagon, which nobody really knew was the plane at that moment. But everybody's cell phone went off. A lot of us were on GETS [the Government Emergency Telephone System]. We had the phones and we were on the special telecom system for emergencies.

FCW: And so those started going off.

FORMAN: Yes. And of course everybody was called out. We started to head back into D.C., to drive in and you couldn't. I got a call from my office at OMB that just said, "We're shutting down everything." The Old Executive Office Building where my office was, was evacuated. They told us: "You need to just go home." And so we turned around and the D.C. area was a gridlock. Everything inside the Beltway was a gridlock. So it took a couple of hours.

FCW: How did the attacks affect your work and the e-government strategy?

FORMAN: GSA arranged a teleconference for us to complete the scoring of the roughly 25 e-government initiatives, presidential e-government initiatives that had business cases. And we spent particular attention talking about the top five projects for government-to-government, because we knew those were all going to be pretty relevant to the recovery. One was getting the public safety wireless network integrated, which of course has now finally come to fruition with FirstNet.

But back then we were getting early reports on the success that New York was having with using mobile devices, back then they were Palm Pilots that had a building information on them. And that was a fraction of the different wireless interoperability initiatives that FEMA, Treasury and Justice had. And that project was to consolidate, put altogether, repurpose that funding so that you would have integrated public safety networks that were accessible via wireless devices. That basically was a shift away from land mobile radio. It took a long time, but I think we'll see that FirstNet is one of the things that's made responsiveness for emergency response and preparedness so much better.

FCW: For you and your team and your community, was there some solace in being able to work on something that was directly relevant to the crisis?

FORMAN: Oh yes, there was. Another business case was grants. Grants.gov came out of that. Because before then it took years, basically two years was the target time to issue a grant. And by the afternoon of September 11, we knew the massive amount of grants that would be needed were in the billions. So the government-to-government initiatives were built to accelerate preparedness and response. And yes, there was solace and focus, I would say. There was an awful lot of focus that afternoon on how our work would help address the country’s needs.

FCW: And how soon were you able to regroup in person and go back to the White House?

FORMAN: I think it was about a week. I don't think we were able to come back in until the following week. And even then at first there was a perimeter, a large perimeter set up around the White House complex. And so you had to have your ID to be able to go through. And then even within our building and same thing in the new executive office building, there were people on the roof, much more physical presence on the roof than was normal, and everybody understood the seriousness. There was a different seriousness and approach when you came into your office I'd say for definitely at least two months as we were looking at everything that needed to be done to respond.

FCW: The public response to the attacks manifested itself to some extent into military enlistment. And I'm wondering at the level of people just wanting to play a part in government and in your world, did you see a response from students, people starting out in their careers, people contemplating new careers, did 9/11 galvanize any activity in that area?

FORMAN: The answer is yes -- all levels. One good example is Norm Lorentz, who was the real first CTO for the federal government. I wanted as part of my organization at OMB to have a CTO for the federal government. And Mitch Daniels [then director of the Office of Management and Budget] granted that. Norm had been CTO for a company called Dice and for the Postal Service before that. And literally he had I think just gotten off the plane in New York because he was commuting from Washington to New York when everything happened. And when he got back, he wanted to have a way to help.

This always happens when there's a crisis, you set up task forces in the government and people come out of the woodwork who want to be on task forces. This is the same thing happened in the pandemic. These task forces are created based on who you know, because the information infrastructure is not in place ahead of the event to respond appropriately. So it becomes a game of finding people who are good people based on the network, which is kind of exactly the wrong approach, but the same thing happened with COVID.

And unfortunately, you never really find the best people because it's all word of mouth and who you know. That doesn't mean you don't find good people. You do find good people, but it's I think one of the inefficiencies in government response to crises.

FCW: And what about the impact on the community of CIOs and federal IT managers? Did September 11 have a galvanizing function on your community that you could speak to?

FORMAN: Yeah, in two areas. One was information as an asset. People understood the impact of siloed systems in basically hurting the ability of the government to respond to citizen needs. And we had a lot of energy in busting down silos within and across departments, primarily across departments. I think the second thing was in enterprise architecture, strangely enough. I ended up calling it modernization blueprints. Many non-technical people understood the importance of architecture in getting agencies and people to work together. So we had people that didn't understand anything about technology that normally would be averse to talking about architecture, suddenly embracing the concept of enterprise architecture as a way to understand how pieces could fit together, business pieces, how agencies could work together, how to get their systems to work together.

A poster child of that was the anthrax scare that was part of the issue back then. We had something like 30 different agency budget requests to redo public health networks. And that's what generated the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT originally. These public health networks were all antiquated and hadn't been modernized. And when we had 30 different programs saying they were going to do it, that was so nonsensical in our understanding post 9/11, that we created an office to drive all those different organizations into an integrated environment.

FCW: Does a crisis environment help foster organizational change?

FORMAN: Yeah. In fact, I think there've been quite a few studies on IT governance that show that a crisis is often the only way you can make progress in IT governance. CIOs either get fired or empowered in a crisis. If you get fired, the next person that comes in gets more power.

And in terms of morale, I think inevitably in the federal IT community and especially among the CIOs there was a sense of working together. You could do more than working within your agency. And I haven't often seen that spirit. It may still be there, but it was such a unique time where the CIOs felt that they were a team, that they were important as a team, and they could do things and have an impact on the public together.

And I just haven't even seen that. Maybe even today, I think most of the CIOs are working within their agencies. Maybe with COVID they felt that they could work together as a team. But like I say, it was such a unique time after 9/11, that it was really impressive to see how CIOs across agencies came together as a team.

NEXT STORY: Quick Hits