Defining the role of technology in fighting waste, fraud, abuse

Technology helps stem the tide of bad spending practices, but there are weaknesses and gaps in agencies' use of it, experts say.

Technology may help agencies stem the tide of waste, fraud and abuse, but sometimes new tools just aren’t enough, according to some experts.

“Technology in terms of transparency is there, and we need to use it,” said Earl Devaney, former chairman of the Recovery Board. “Quite frankly, some of the ideas floating around now that I read about poolside don’t talk a lot about transparency – it’s almost like the word has gone away. [There’s] a lot of talk around technology to cure the accountability piece, but the transparency piece has been sort of missing.”

Newer technologies such as cloud computing, mobile devices and geospatial services have brought new meaning to transparency, Devaney noted at a Sept. 6 breakfast briefing titled “The Watchful Eye: Preventing Waste, Fraud and Abuse,” organized by FedInsider. Data can be quickly displayed and quality controlled, as seen with Recovery.gov, he said. The website created what he said were unparalleled levels of transparency, with technology that allowed citizens to add their zip codes to drill down to their own neighborhoods and see where their tax dollars went, he said.

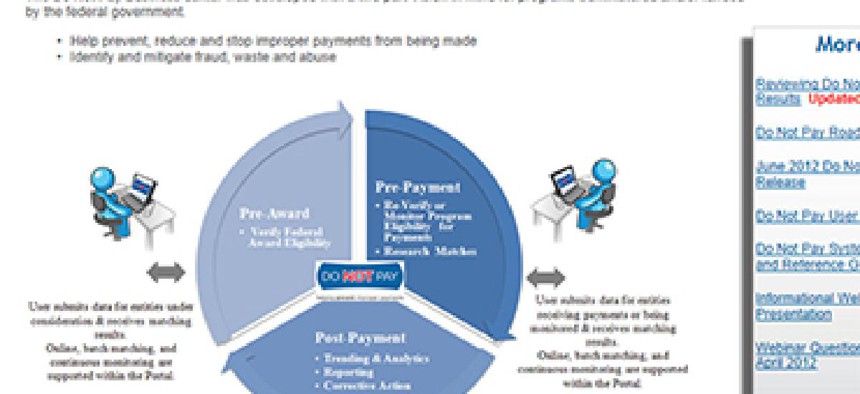

The Treasury Department’s Do Not Pay List -- a centralized repository that pulls data from five different sources -- was created in response to the 2010 presidential memorandum that directed agencies to enhance payment accuracy. The Do Not Pay Business Center within Treasury’s Bureau of the Public Debt was created a year later as part of the same initiative to prevent, reduce and stop improper payments, as well as identify and mitigate fraud, waste and abuse.

The center's goal over the next 18 months is to expand the number of federal agencies using Do Not Pay, from 17 to 24, said Tom Vannoy, Do Not Pay program manager at the Bureau of the Public Debt. “That’s not a stretch by any means over the next 12 to 18 months, but a goal we feel we can meet fairly shortly,” he said.

Vannoy’s office is also looking to increase the data sources available on the Do Not Pay online portal, which underwent a makeover in June 2012 to provide new features such as batch matching and continuous monitoring. The idea is to go from eight data sources to 14, and add high value to the greatest number of users, Vannoy said.

Continuous monitoring “adds a twist on the batch-matching process,” he said. For example, one agency regularly sends its list of beneficiaries or pension recipients to the Do Not Pay Business Center, which then matches the information against the various data sources to determine whether an individual is deceased. Depending on the information from the data sources, a payment can then either be stopped or continued.

“We’re trying to get that [information] in front of all the newspaper stories that come out regularly where we’ve been paying someone for 25 years because the son or the daughter accessed the account and kept the money coming and never reported it,” Vannoy said.

Citing a study by the Association of Government Accountants that examined the use of analytics governmentwide, fellow panelist Kevin Greer, executive director at Accenture’s Federal Finance & Performance Management Practice, said improper payments comprise only a small percentage of all payments; 95 percent of all payments are accurate. “It’s the 5 percent that add up to a significant large number,” Greer said. However, not all improper payments are fraudulent. Some are made in error, and some simply lack the documentation that would support the validity of the transaction.

Agencies are more focused on recovering improper payments than preventing them, but the success rate for recovery is only about 10 percent, he said. “So the pay-and-chase model is particularly challenging," Greer said.

Most improper payments occur in eligibility programs where agencies such as the Social Security Administration are paying large amounts to members of the public on a regular basis as part of particular programs. SSA, for example, pays out $8 million per month to Social Security recipients, and an estimated 10 percent are improper payments. Unreported earnings make up most of the fraudulent claims.

Resolving improper payments is difficult, partly because it’s challenging to reconcile information prior to payment. Another factor to consider is that data is dispersed from various agencies and siloed systems, Greer said.

Although agencies may have the latest and the best technology at their disposal, they are still fighting an uphill battle, Greer noted.

“We actually think the problem is getting worse, because the quantity of data seems to be increasing and the quality continues to be bad," he said. “Data is also becoming decentralized in many organizations; legacy systems and processes aren’t integrated or talking to one another. Also, fraud is becoming more and more sophisticated; [criminals are] learning the business rules, and they know how to work around those.”