2020 census is counting on technology

The goal is to have at least 60 percent of the next decennial count's responses submitted electronically.

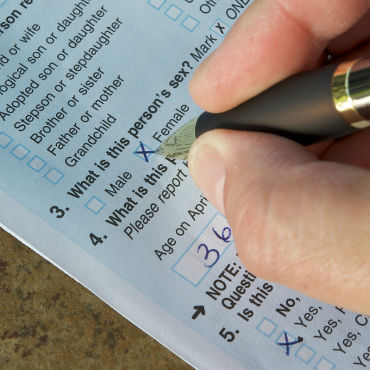

Census Bureau officials want to do away with paper-based surveys for the majority of Americans.

The well-documented problems with federal IT procurement are causing some to rethink grand-scale projects, but in at least one corner of the bureaucracy, planning continues for a dramatic increase in online interaction with the public.

The Census Bureau's goal is to have at least 60 percent of responses for the 2020 census submitted electronically, driving down the cost for postage, paper and employees' time, said CIO Brian McGrath. Given the size and scope of the survey, not to mention its constitutional mandate, bureau officials have already begun looking into how the goal can be achieved.

The decennial count's massive data collection presents a twofold security challenge familiar to anyone who has followed the HealthCare.gov saga: ensuring data integrity while protecting the privacy of individuals' information.

"I think the biggest challenge to make an Internet self-response option successful is to gain the trust and confidence of the American public that the data that they are providing online is secure and it's safe, both in transit and in our databases," McGrath said. "The other challenge is one of communication, which is getting the word out to the American public that an [Internet] option is available."

The bureau is buying URLs that officials fear could otherwise be exploited by hackers trying to set up phony sites with similar names. But no matter how many precautions are taken, some people will not want to report their information online.

"I think we have a sense that some people are concerned about privacy and about their personal information, and it may be that those individuals are simply not going to want to do this online," said Scott Keeter, director of survey research at the Pew Research Center.

The solution is to give those individuals access to traditional means -- paper or in-person interviews -- to share their information.

Ensuring data integrity

The other side of the security equation is figuring out how the government can guarantee that the data it is receiving is correct.

"We have to...ensure that the responses we receive are in fact legitimate responses and we don't receive multiple responses from the same household," McGrath said. "But in many ways, it's the same problem that we faced in 2010, where someone could have filled out multiple forms."

He said the bureau will likely use some sort of cloud-based solution to store the data. "I think from a cost and efficiency perspective, the public cloud is going to play a significant role in the architecture for the 2020 online solution."

But whether to build an in-house cloud or contract with a private-sector provider has yet to be determined. McGrath said any procurement activity will probably happen in fiscal 2017 or 2018.

"Clearly, we would need to augment staff to build a survey of the size, scope and complexity of the 2020 decennial census, with [additional] contract resources," he said.

Time to test

As the calendar flips to another year, other questions remain unanswered, such as whether the online survey would be available nationwide simultaneously or only in certain areas during certain times to regulate the massive input of data.

And then there's the activity that has bedeviled HealthCare.gov: testing. Although McGrath recognizes that it is difficult, if not impossible, to simulate the size and scope of the census, the bureau has several opportunities to test an Internet response option before the actual survey.

About half of the responses to the bureau's American Community Survey, which samples a small percentage of the population every year, have come via the Internet, and McGrath said the 2017 economic census will be paperless. Additionally, the bureau conducts about 100 surveys online annually for itself and other agencies.

"We'll engage in a whole series of performance-testing activities to simulate the load," he said.

The American Community Survey has more questions and might seem more intrusive than the census, Keeter said. In that respect, positive results from that survey suggest that scaling the census for the entire population is not an insurmountable task.

"As I understand it from people who do this kind of work, the problem of scaling a survey up to deal with large demand is one that's pretty well understood by data scientists," Keeter said.

Although he could not address the feasibility of the bureau's goal for online responses, he was confident that officials were taking the right approach and had the track record to support it.

"There's reason to believe that with proper planning -- and that's, of course, an important caveat -- the Census [Bureau] will be able to allocate enough available server capacity and other computing capacities to handle this," he said.

Keeter said the task faced by the bureau is relatively simple compared with the one HealthCare.gov confronted.

"It turned out that the capacity issue was not fundamentally the major source of [HealthCare.gov's] problems," he said. "It was a problem in the very beginning, but it had to do more with the integration of multiple datasets, the need to look up information from existing government databases and to integrate it in a way that really was beyond the scope of anything that I think any of the folks working on it had anticipated or experienced before. By contrast, the census task is much simpler. They're essentially administering a survey, and the extent to which the need to have the survey itself connect to other databases is considerably smaller, if it's necessary at all."

Considering BYOD

The Census Bureau has some experience in online data collection in the field. Census takers used purpose-built handheld devices to validate addresses for the 2010 census. But allowing them to gather data using their personal devices was considered a technological bridge too far last time around.

"In 2010...there were two operations that the [purpose-built] device was intended to accommodate," McGrath said. "The first was address canvassing, where we went out to every address across the country to validate the address, and the technology and the handheld did work, it actually worked rather effectively for that operation. Where we experienced some complexities was around the enumeration operation, where we would've used the device to actually go out and collect the response."

This time could be different. McGrath said bureau officials are considering a system that would allow census takers to use their own devices to collect data, which would immediately be transmitted to a cloud or other storage infrastructure, thereby alleviating security concerns.

"What we can do is secure the application and the data that they put on that device and certainly ensure the security of the data in transit between the device and our infrastructure," McGrath said.

Although that might make people feel more secure, there is the question of whether census workers will want to give the government access to their personal smartphones and tablet PCs.

"If we're using personally owned equipment, what, if any, concerns do the employees have with the government having access, and what type of access would we have to that device to ensure the security, integrity and availability of the data?" Keeter asked.

Answers to those questions have yet to be worked out.