Lost data prompts need for secretive stash

Options abound for encrypting data in enterprise and mobile storage devices.

Recent data loss incidents have called attention to the need for encrypting data housed on agency storage devices, whether they are mammoth tape libraries or humble USB storage devices.

In May, the Department of Veterans Affairs reported the theft of a laptop computer and disks containing personal information on 26.5 million veterans. In another incident that month, a backup tape from a VA general counsel’s regional office went missing. In September, the Commerce Department disclosed the loss of more than 1,100 laptops during the last five years, 246 of which contained personally identifiable information.

Industry observers say government agencies are becoming more interested in encrypting stored data, also called data at rest. Some agencies, particularly in the defense sector, already use encryption technology to guard data.

But a purchasing wave has not yet materialized. A major obstacle is the lack of a specific regulatory guideline for encrypting stored data, said Bill Hartman, vice president of technology and architecture at Sanz, a storage integrator and consulting firm. He said the Office of Management and Budget’s security guidance calls for agencies to protect data at rest, but it does not mention encryption.

When agencies are ready to embark on encryption, they have many choices for protecting data on enterprise storage devices, computers and other mobile platforms. Here is an overview of the options.

Data loss concerns arise whenever a data-storing device leaves a government facility. Tapes used in backup and archiving operations fit that category. Agencies often ship tapes to an off-site vault for safekeeping, but they sometimes disappear in transit.

Storage administrators have several options for protecting data on tape.

Software-based encryption, for example, has been available for a while through enterprise backup software vendors. EMC’s Legato NetWorker and IBM’s Tivoli Storage Manager provide encryption as a standard feature. Symantec’s Veritas NetBackup offers encryption as an additional option.

Such backup software solutions generally encrypt data on the PCs or servers that created it, then they transfer the data across the network and store it on tape in an encrypted format. The software approach consumes considerable processor resources on the source computer and raises performance issues, industry analysts say.

Software encryption “is notoriously slow, and when you start thinking about higher-end encryption algorithms, it’s going to get slower,” said Jon Oltsik, senior analyst for information security at the Enterprise Strategy Group.

Stand-alone encryption appliances provide a performance-boosting alternative. Appliances offer a hardware-based solution that encrypts data as it moves from computers to a tape library or other storage device. Encryption appliance vendors include NeoScale Systems, Network Appliance’s Decru unit and Vormetric.

Appliance vendors generally support up to 256-bit Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) encryption. Products from NeoScale, Decru and Vormetric comply with Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 140-2.

Hartman said appliances offer a speed advantage over tape and tend to be the best choice for consolidated storage settings.

But appliances have some limitations. Customers who wish to encrypt every tape device in a highly decentralized environment may find software a less expensive option that is easier to manage, Hartman said.

“If you have large numbers of tape drives, you need to buy many more appliances,” he said, adding that a tape repository with 10 drives might need two or three appliances to provide adequate bandwidth for the large data flow.

Kevin Brown, vice president of marketing at Decru, said the company aims to provide appliances that can handle peak throughput during backup operations. He said Decru’s 10-port DataFort FC1020 appliance can handle about 20 Linear Tape-Open-2 tape drives, depending on the throughput of the tape devices. LTO is a popular midrange tape format.

A new wrinkle in tape security has emerged — some storage devices can handle data encryption duties themselves.

In September, Sun Microsystems unveiled its StorageTek Crypto-Ready T10000 tape drive and Crypto Key Management Station. The solution uses 256-bit AES encryption, and a Sun StorageTek spokeswoman said the company anticipates adding FIPS 140-2 certification in 2007. StorageTek T1000 tape drives start at $37,000, and the encryption option for the Crypto-Ready T10000 tape drive costs $5,000.

Also in September, IBM introduced its System Storage TS1120 encryption drive, which supports 256-bit AES encryption. Brad Johns, program director for storage software and tape marketing at IBM, said the encryption capability resides on an application-specific integrated circuit in the drive. Johns said IBM will begin the process of obtaining FIPS 140-2 certification later this year or early next year. Encryption comes standard with newly ordered tape drives, with prices starting at $35,500. Customers who previously installed TS1120 can upgrade it to include the encryption feature. That upgrade costs $5,000.

Spectra Logic, meanwhile, has been shipping tape libraries with 256-bit AES encryption capability since May. The company’s T950 and T120 products, which write to tape and disk, employ hardware-based encryption. An encryption chip resides within a tape library’s interface module rather than at the drive level, said Brian Grainger, federal sales vice president at Spectra Logic. The company’s BlueScale software handles the key management.

Spectra Logic does not charge for encryption with its BlueScale standard edition offering. The standard edition, which lets users generate a single key in the library, targets smaller customers and those who want to experiment with encryption. BlueScale’s professional edition, which costs $12,500 for the T120 and $25,000 for the T950, lets customers generate multiple keys for more robust environments, Grainger said.

Encryption will also appear on midrange tape drives in addition to higher-end drives and libraries. Earlier this year, the LTO Program said its technology provider companies plan to include encryption in LTO-4 tape drive specifications. Those companies are Hewlett-Packard, IBM and Quantum.

Performance is not the only advantage of device-level encryption. “The strong point is that it is a much less expensive solution,” said Paul Simons, senior solution architect at Apptis. He added that preliminary vendor pricing starts at $5,000 for an encryption-equipped tape drive, while an encryption appliance could cost five times as much.

Encryption appliances generally cost more than $20,000.

Simons said he believes the cost of encryption will continue to decline because of its availability in chipset form. “The price will steadily erode until it becomes a minor component of the overall cost of a disk subsystem or tape device,” he said.

Robert Rosen, president of Share, an IBM user group, and chief information officer at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, said he believes IT shops will move toward built-in encryption in the coming years.

Rosen said timing is the main issue now.

Chuck Berninger, director of platform operations at BAE IT, the integration unit of defense contractor BAE Systems, said the company plans to deploy Spectra Logic’s encryption feature next year on its T950 tape library. “Once you get into the hardware-based [encryption], you are offloading that function into electronics that can do that a lot faster than software,” Berninger said.

Oltsik said economics will drive cryptographic processing to the device level. “It has got to evolve in that direction” he said, adding that the hard part will be managing multiple devices and cryptographic keys. “You have to centralize that.”

Some industry executives say the encryption appliances’ key management features may play that centralized management role. “We have opened up key management” application program interfaces, Brown said. Quantum tape libraries, for example, already integrate with Decru’s key management platform.

Encryption appliances will also continue to play a role with older systems, Oltsik said. He said an organization is more likely to buy an appliance than replace all of its previously installed tape gear.

In recent years, more government agencies have converted from tape to disk for their backup and archival strategies. The data protection schemes for disk mirror those for tape. Agencies can use enterprise backup software or encryption appliances with disk-based virtual tape libraries.

Device-level encryption for disks is less common. Fujitsu Computer Systems, however, ships its Eternus8000 and Eternus4000 disk arrays with 128-bit AES encryption. Pricing starts at $24,500.

Industry executives say mobile PCs and their internal and external storage devices are another important vulnerability.

As with enterprise storage, software-based solutions initially dominated this market, too. Steven Sprague, president and chief executive officer of Wave Systems, said full-disk encryption software has been available for many years. Encryption software installed on a PC intercepts operating system commands and monitors all data traffic, encrypting data when writing to disk and decrypting it when a user needs to read the data, Sprague said.

Examples of full-disk encryption products includes GuardianEdge Technologies’ Encryption Anywhere Hard Disk, PGP’s Whole Disk Encryption, Pointsec Mobile Technologies’ Pointsec for PC and Pointsec for Linux, SafeNet’s ProtectDrive, and Ultimaco Safeware’s SafeGuard Easy.

Sprague, whose company makes software aimed at the trusted computing market, said full-disk encryption slows PCs’ performance, decreasing it by as much as 30 percent.

Bob Egner, a vice president at Pointsec, said the company’s customers experience a performance change of less than 3 percent. “There’s no perceptible performance change,” he said of the company’s products, which use 256-bit AES encryption.

But Hartman said the enterprisewide use of encryption across desktop and laptop PCs remains uncommon. Instead, most organizations prefer to limit local access to data via physical security approaches, such as the Defense Department’s Common Access Card, he said. “I’m not seeing too much encryption of data at rest,” Hartman said.

Microsoft’s BitLocker full-drive encryption feature, which will be part of high-end versions of the upcoming Vista operating system, could change that picture. Hartman said he thinks BitLocker, will make encryption more commercially available to the rest of the world.”

Industry analysts and vendors, however, have found gaps in BitLocker’s encryption. BitLocker doesn’t offer a full data-at-rest encryption solution, Simons said.

Andy Solterbeck, vice president and general manager of the Commercial Enterprise Business Unit at SafeNet, said BitLocker only supports Vista machines and focuses protection on the C: drive. The encryption does not cover removable storage devices, such as USB flash drives.

Encryption software vendors, however, offer products that extend protection to other devices and storage platforms. Pointsec, for example, markets products that cover smart phones, personal digital assistants and removable storage devices. Similarly, GuardianEdge and SafeNet have encryption products for portable media.

File-level encryption is another security hole that some vendors aim to plug.

Joe Sturonas, chief technology officer of PKWARE, said full-disk encryption can help protect data on stolen laptops. But he said such solutions fail to address situations in which an organization wants to block systems administrators or other employees from viewing the contents of particular files.

PKWARE’s SecureZip secures files with 256-bit AES encryption. Other vendors in the file and folder encryption space include GuardianEdge and SafeNet.

The various encryption software products tend to hold keys in software, but some have begun using Trusted Platform Module chips built into a PC’s motherboard, said Sprague, whose company makes TPM management software.

TPM dramatically strengthens software-based full-disk encryption solutions because the key is stored on hardware — the chip — that is separate from the hard drive that stores the rest of the data, Sprague said. That keeps it out of reach of a hacker who might gain access to the computer’s hard drive.

Device-level encryption, as with enterprise storage, has also begun to make its way into PC storage. Seagate announced last month that it will manufacture hard drives with full-disk encryption built in. The company’s DriveTrust Technology will appear in its Momentus 5400 FDE.2 for laptops. It plans to introduce that drive in the first quarter of 2007.

Hitachi also plans to release a full-disk encryption product in 2007, Sprague said.

Some analysts expect a bifurcation in the encryption market, as general users will manage with software-based encryption and users with sensitive data will opt for device-level encryption.

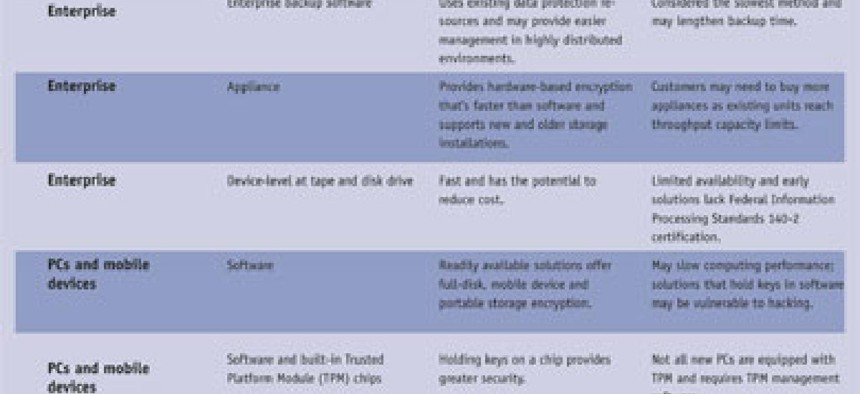

Protection schemes

Click here to enlarge chart (.pdf).

Experiment with encryption

Protecting PCs, mobile devices

Trusted Platform chips

Protection schemes

Click here to enlarge chart (.pdf).

Experiment with encryption

Protecting PCs, mobile devices

Trusted Platform chips