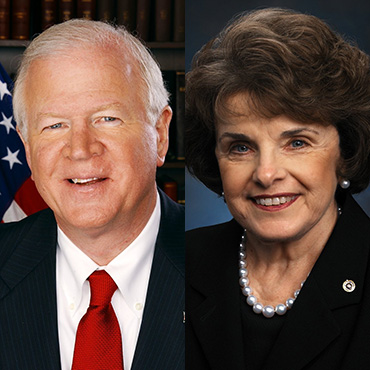

Feinstein, Chambliss: We can pass a cyber bill during lame duck

The chair and ranking member of the Senate Intelligence Committee say they've addressed privacy and liability concerns, and predict both chambers can move cyber legislation after the election.

Sens. Saxby Chambliss (R-Ga.) and Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) claim their cyber legislation has a solid chance of passing during the lame duck session.

The Senate Intelligence Committee's top Democrat and Republican made an eleventh-hour pitch for Congress to pass their cybersecurity information-sharing bill during next month's lame-duck session.

Sens. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) and Saxby Chambliss (R-Ga.) told an Oct. 28 conference hosted by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that their cybersecurity bill has a good chance of passing in the lame duck because compliance with the bill would be voluntary and not mandatory. Differing opinions on the proper approach to public-private information-sharing have killed several previous cyber bills in 2012 and 2013.

Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Mich.), chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, has said he is ready to convene a conference committee with the Senate during the lame-duck session to work out a final version. The House passed its cybersecurity bill, which the White House threatened to veto, in April 2013.

Chambliss has said the quartet of Intelligence Committee leaders (which includes Maryland Democratic Rep. Dutch Ruppersberger) have collaborated more closely than previous groups. And Chambliss and Rogers are retiring at the end of this term, lending urgency to the effort. But given the crowded legislative calendar, partisan gridlock and the fact that the Obama administration may, as Feinstein noted Oct. 28, prioritize surveillance reform over a cyber bill, there are plenty of ways that a cybersecurity information-sharing bill could still stall in the lame duck.

The Feinstein-Chambliss bill would authorize a centralized process at the Department of Homeland Security by which private firms could share threat information with the government without legal liability. That information would then be shared simultaneously with relevant federal agencies. The DHS secretary would have to confirm to Congress that that process is functional before it is implemented.

Supporters of the bill say the possibility of legal repercussions for firms that share confidential information with the government has undercut cybersecurity. That the bill addresses this liability issue is one reason the U.S. Chamber of Commerce supports it.

The bill also would allow firms with written consent from a federal agency to help an agency repel malware attacks and other cyber threats via "countermeasures," which are defined as techniques and technologies that help protect an information system. Mark Seward, senior director of public sector solutions marketing at Splunk, a big-data analytics firm, has said that data collected through countermeasures would provide fodder for information-sharing across the private sector, and between the private sector and government.

The Senate Intelligence Committee approved the measure by a 12-3 vote in July, but it has yet to see the Senate floor. "I think if we can get this up on the floor, I believe we can pass it," Feinstein said.

A coalition of privacy and online groups oppose the bill, arguing that it would do less to protect civil liberties than a 2012 Senate bill that failed, in part, because of opposition from the Chamber of Commerce.

Starting in mid-November, Congress will reconvene for several weeks with a crowded docket of bills and issues to consider. "I have implored [Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid] that if there is one piece of legislation that needs to be completed between now and the end of the year, this is it," Chambliss said.

Chambliss and Feinstein have sparred over previous cybersecurity legislation, and pointed to their cooperation this time around as evidence the bill is both pragmatic and passable. "We [did] not want to produce something that cannot get a vote," Feinstein said.

Yet even as Chambliss stressed the urgency of passing the bill, he said establishing a public-private mechanism for sharing cyber threats is a long-term endeavor.

"It's important that we put language in this bill that allows flexibility," he said. "This is not a short-term project from our standpoint."

Given how quickly cybersecurity technology changes, he added, "we want to make sure that 10 years from now that there's flexibility in the legislative language that allows the public sector and the private sector ... to adjust to what technology comes forward in the intervening timeframe."

NEXT STORY: Cape May-Lewes Ferry Hit by Payment Card Breach