Joyce: Civilian cyber could use more discipline

The top White House cybersecurity adviser suggests civilian agencies could take a page from the Pentagon's handbook.

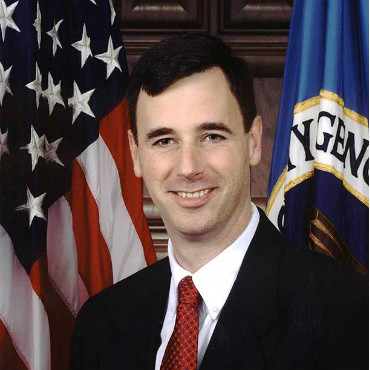

White House cyber adviser Rob Joyce thinks that civilian agencies could use some of the Pentagon's cybersecurity rigor.

If civilian federal agencies want to succeed at cyber, they should take a page out of the Defense Department's book and quit deliberating so much, according to White House cyber coordinator Rob Joyce.

Coming from the National Security Agency and working with Cyber Command, Joyce, who was speaking at Nov. 9 Defense One Summit in Washington, D.C., said being on the civilian side has been a learning experience in decision-making and leadership.

"One of the best things we got out of CyberCom was really a centralization of the Defense Department where now they have a four-star commander who can order things quicker," Joyce said. "When they decided they wanted to get [rid of] Kaspersky, somebody writes an order and they execute. With the civilian side, we knew we needed to do it, but we studied the problem a bit, we get the lawyers involved in the binding operational directive and it was harder."

The same thing happened in the Department of Homeland Security went to adopt DMARC (Domain-based Messaging Authentication Reporting and Conformance), he said. "It took a long time because they studied the impacts of the process of those issuances."

Ideally, Joyce would like the civilian agencies to adopt more of military commander's approach to cyber implementation as they beef up security and hygiene practices.

"I'd like to see us get a little more directive with the federal IT infrastructure," he said.

"We have to be able to know what's in the infrastructure, in what state it is, to be able to defend it," he continued. "You can't defend that which you don't know. So a key part of this is getting to point where up to date understandings of what's been initiated in the infrastructure, what's been added, what's been removed, and when there's a new vulnerability or flaw."

Part of that onus of implementation across the government, however, is on the federal cyber executives – of which there are few because of a large number of vacancies.

Joyce couldn't affirm whether all of the cyber and technology positions would get filled eventually, but said "it's not an intentional emptiness today and not an intentional decision to keep those [positions] empty going forward. It's more stacking up the nominations and clearing the decks of the senior most leaders and ambassadors that we've got to get through and then the next level follows."

Not having permanent federal cyber leaders to lean on has taken a toll on his job, however.

Joyce said having those roles filled by "acting" cyber leaders has been "challenged a bit to get some of the most decisive change in place," though he added that the new crew that comes in will be better able to buck the status quo. The careerists already in place have a wealth of knowledge that has been valuable, he said, and he vowed to continue to push to make sure that "just because they're experts, they don't rest on the status quo."

As for federal CIO and CISO nominations, Joyce said the administration is looking for people who understand how government works, and disruptors, people from industry, who know where the technology innovation is going.

"You'll see a lot of the cyber people float into the nominations and we need those people. Those are important jobs," he said.