Fed contractors want thorough overhaul of clearance processing

Poll details many faults in ‘wholesale systemic failure’

More than half of government contractors say the security clearance process has gotten worse or not improved at all in the past year, according to a new poll conducted by Federal Computer Week and its industry partners.

The May survey sought to assess the effects on industry and government of the Defense Security Service’s decision in April to suspend the processing of security clearances because the agency had run out of funds to pay for them.

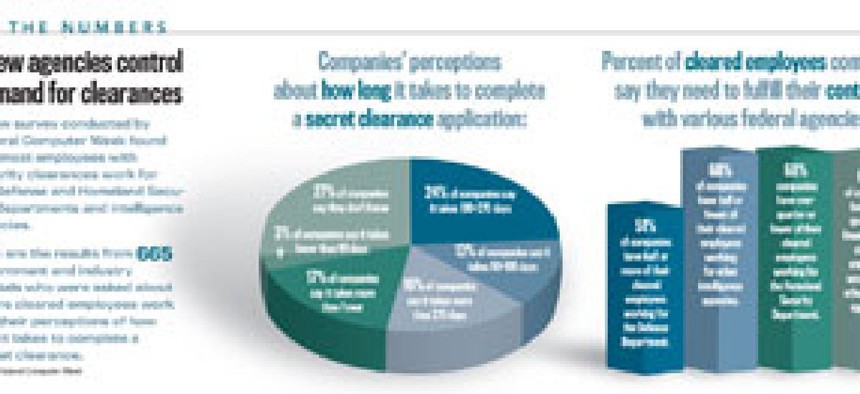

The survey analyzed 665 responses from industry and government officials. The pool included 280 respondents from large businesses, 110 from midsize businesses, 180 from small or other designated businesses, and 95 from government agencies.

While 33 percent of contractors said an interim clearance now takes about 30 days, another 25 percent put the time at more than 90 days. And 40 percent said it takes more than a full year to adjudicate a top-secret clearance.

More than three-fourths of the industry respondents agreed that requests for cleared employees have increased “greatly” (51 percent) or “somewhat” (26 percent) in the past five years.

Trey Hodgkins, director of the Information Technology Association of America’s defense committee, said the survey supports “the anecdotal information we’ve been hearing from our members about the conditions they’re experiencing and the problems they’ve faced now for several years.”

Hodgkins said the poll and the backlog of 300,000 clearance requests show that processing conditions are getting worse, not better.

John Stenberg, facilities and contracting security officer at CACI Technology in Eatontown, N.J., near Fort Monmouth, said the clearance process has a great impact on the company because 95 percent or more of the staff needs a specialized top-secret clearance. “We either have to hire cleared people, which is very difficult, or we just have people [who are] not able to work,” he said.

Although the on-again, off-again clearance process has not affected the company’s work, he said, “the longer this continues, that is going to happen.”

Hodgkins said the Office of Personnel Management is partially to blame for the backlog and delays “because they largely continue to use a paperwork-intensive investigative process” that dates to the 1950s.

He said he hopes lawmakers will use the moratorium as a signal that it is time to correct “this wholesale systemic failure across the board.”

The processing bottleneck has given cleared workers a bargaining chip when it comes to salary negotiations. Slightly more than half of the federal IT contractors polled said they are now paying a salary premium or other benefits to attract, hire or retain workers with security clearances. Of those companies, 73 percent put the premium at 5 percent to 25 percent. And 60 percent of the industry respondents said premiums are increasing.

Currently, contractors pay no fee for processing clearance requests. Since February 2005, DSS pays OPM to conduct most nonintelligence-related clearances, which can range from about $400 for a standard background check to more than $4,000 for a top-secret clearance. But only 25 percent of those polled thought their employer would be willing to pay all or a portion of a security investigation fee.

“If industry is going to pay for it, then we’re going to pay for a process that works,” Hodgkins said.

Valerie Perlowitz, president and chief executive officer of Reliable Integration Services, said she wondered how paying a fee would help. “If we have so many clearances we can’t keep up with now, what is paying for it going to solve?” she asked.

Perlowitz said a payment plan could have negative effects on small companies like hers. Large firms have more money to spend on getting employees cleared, she said. “Does that mean they [would] get priority in the queue before me?”

Perlowitz said paying for clearances could result in a spoils system in which only the wealthiest companies could win contracts that required hiring cleared employees.

However, government respondents were mostly in the dark about such issues, with 83 percent of the agency respondents saying they did not know what a top-secret clearance costs and 66 percent saying they did not know whether their agency or department paid a premium for investigations. In addition, 64 percent said they did not know whether their agency or department had sufficient funding in fiscal 2006 to meet its needs for cleared employees.

The findings also underscore how unhappy contractors are with current clearance reciprocity and reinvestigation procedures. Fifty-eight percent said applications for periodic reinvestigations are taking longer to process or are not being processed at all.

A third of the industry respondents said cleared workers going from one contract to another have to undergo a completely new clearance, and half said additional clearance requirements often extended the process.

Perlowitz said it takes anywhere from four to six months for someone with one agency’s clearance to be cleared for another agency. “Why can’t we standardize the information that needs to be gathered so agencies will accept each other’s clearances?” she asked.

“How do I get to the point where I can staff these new contracts without having to put people on overhead for a matter of months, which in effect is going to raise my rates?” she asked. “It’s either that or I become uncompetitive and I have to leave the marketplace. I don’t want to do that.”

The time has come for someone to significantly streamline the process, she said. But when asked how well OPM deals with clearance problems, only 4 percent of the survey respondents said the agency is “very helpful.” Twelve percent said OPM provides no help at all, and only 16 percent thought it was “somewhat helpful.”

“Clearances don’t end, they just get old,” said Air Force Master Sgt. Richard Vaughn, chief of security at the Joint Information Operations Center, a Defense Department facility in San Antonio that includes the four branches of the military, some 100 civilians and about 150 government contractors.

He suggested that DOD could ease the logjam by extending the term of a clearance from five years to 10 before requiring a periodic reinvestigation. “It’s been done in the past,” Vaughn said.

The industry groups whose members participated in the FCW survey included the Aerospace Industry Association, AFCEA International, the Associated General Contractors of America, the Association of Old Crows, the Contract Services Association, ITAA, the Intelligence and National Security Alliance, the National Defense Industrial Association and the Professional Services Council.

NEXT STORY: SBA seeks to help women earn contracts