A long haul for freight security

Cargo security plans for trucking, maritime and aviation sectors seek a balance between homeland security and efficient commerce.

The task of securing cargo in the United States involves a complex web of interconnected transportation systems, governmental jurisdictions and industry players. A big question for the government is how can it improve cargo security without impeding the flow of commerce.

The country’s transportation network moves about 43 million tons of goods worth $29 billion on an average day, according to the Transportation Department’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Trucks account for most of the shipping. The bureau’s commercial freight activity report for 2002 shows that trucks hauled more than 60 percent of U.S. cargo.

Container ships and other oceangoing vessels contribute to the security risk.DOT’s Maritime Administration reports that ships made 61,047 U.S. port calls in 2005. The average cargo load per call was 50,083 deadweight tons. Airborne shipments through Federal Express, United Parcel Service and commercial airlines play a smaller role, but they also raise security concerns.

Homeland Security Department agencies such as the Coast Guard, Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency run a number of cargo transportation security programs. State and local governments and port authorities also have security initiatives.

All of them face numerous challenges in providing cargo security. Industry groups are concerned that some security measures might be impractical to implement because of the volume and complexity of trade. Trade experts agree that the task of sharing data and providing security across all modes of transportation will test the technical and organizational capacities of government and industry.

“We really have to sit down and understand the transportation system,” said Justin Russell, director of port security for General Dynamics Information Technology and a veteran of the Coast Guard. “If we focus on one mode,…we will get to the point where we are hindering commerce or not effectively dealing with homeland security,” he said.

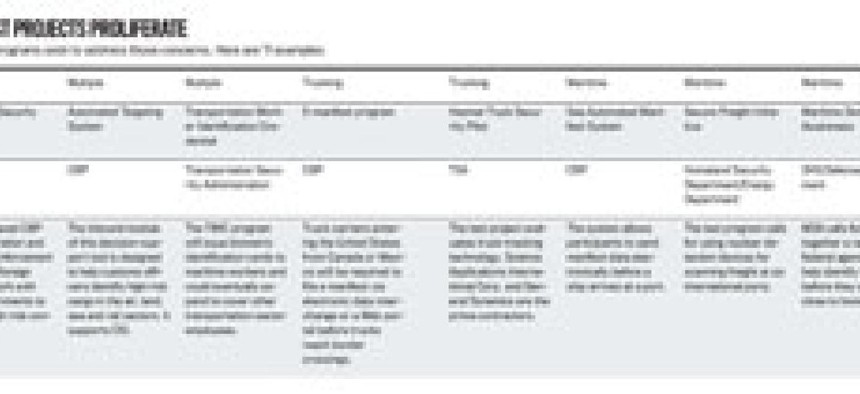

Click here to enlarge chart (.pdf).

Trucking: Manifest destiny

Many homeland security efforts focus on trucking, which is the dominant mode of freight hauling in the CBP’s e-Manifest program. It requires trucks entering the United States from Canada or Mexico to file an electronic manifest using the agency’s Automated Commercial Environment (ACE). The manifest displays information about the type of goods being shipped, the driver and the truck’s planned route.

The e-Manifest program was initially voluntary but became mandatory Jan. 25 for all border crossings in Washington, Arizona and some entry points in North Dakota. Border crossings in California, Texas and New Mexico are next on the mandatory list.

Lou Samenfink, executive director of the cargo systems processing office at CBP, said the program improves security because information gleaned from the manifests can be compared with terrorist watch lists. That type of comparison bogs down when it depends on paper manifests and manual data entry.

About 4 percent of all trucks arriving in the United States voluntarily participated in e-Manifest at the beginning of January, Samenfink said.

“We’ve had pretty lackluster voluntary participation,” he said. Then the satellite radio services Sirius and XM Radio, which are popular with truck drivers, aired spots to publicize e-Manifest. Participation increased to 9 percent of arriving trucks at the end of January.

The e-Manifest center uses electronic data interchange (EDI) and a Web portal. Truck carriers can file manifests via EDI, or they can open a free account and file them at an e-Manifest portal. Samenfink said trucking companies file the documentation themselves or use a service provider.

Regardless of how they arrive, e-manifests facilitate commerce and improve security, experts say. Because the e-manifests arrive at the border ahead of the vehicle, truckers can rapidly clear customs. The manifest isn’t the only item that authorities check at the border, Samenfink said. But having manifests arrive early can speed security processing. The electronically assisted procedure reduced the time that trucks usually require to clear the primary customs check at Detroit from 105 seconds to 73 seconds, Samenfink said.

However, despite such examples of success, other factors often complicate the government’s attempts to regulate ground transportation.

“You can’t regulate when the client wants something,” said Don Rondeau, senior director and homeland security lead at Alion Science and Technology.

For example, a truck driver might be asked to pick up and transport cargo that was not recorded on the original manifest. The route a driver takes might also change during the trip. Rondeau said the government typically regulates ground transportation in the same way it governs airlines. Air carriers file a predetermined flight plan and a manifest that doesn’t change, he said.

The e-Manifest program, however, provides a degree of flexibility for changes. Carriers or their service bureaus can update routes and make cargo changes using an amendment process, for example.

As e-Manifest moves into full implementation, other trucking security efforts are just beginning. TSA awarded two contracts in 2005 to General Dynamics Advanced Information Systems and Science Applications International Corp. for the agency’s Hazmat Truck Security Pilot program.

SAIC evaluated truck-tracking solutions and selected seven vendors — PeopleNet, Safefreight Technology, TrackStar International, Qualcomm, SkyBitz, GE Tip and TransCore — in the project’s first phase. Most of the vendors used Global Positioning System transceivers on trucks to track their location.

General Dynamics established a trucktracking center in Buffalo, N.Y., and created an interface to collect alert and tracking information from commercial tracking systems. A TSA spokeswoman said a demonstration of the truck tracking system is scheduled for September.

Ports: Scanning the globe

CBP estimates that more than 11 million shipboard containers enter the United States each year. Recent activity in Congress has focused on scanning containers for radiological materials before they leave foreign ports.

An anti-terrorism bill that cleared the House in January contains language that woul require international ports to scan every container bound for the United States. Large ports would have three years to comply. Smaller ports would face a five-year deadline.

Meanwhile, industry executives say the legislation’s 100 percent scanning requirement is impractical.

“It’s very difficult to see how this would work,” said Allen Thompson, vice president of global supply chain policy at the Retail Industry Leadership Association. Thompson said the mandate relies on technology that is in development and would require a significant increase in port employees to analyze the scan results. The scanning initiative also would necessitate agreements with host nations, he added.

Russell said 100 percent scanning is unrealistic and a hindrance to commerce. Container scanning requires a risk-based management approach, he said. Quantifying risk and prioritizing vulnerabilities would mean assessing which containers present the most risk and scanning only those rather than scanning ever unit.

“Any security expert will tell you that risk management is the appropriate way to do this,” Thompson said. The House bill omits risk management, he said. “You are assuming that every container is a threat when the overwhelming percentage of containers coming into this country is legitimate.”

In mid-February, the anti-terrorism bill and its scanning provision had not come up for debate in the Senate. Meanwhile, the government will soon begin early-phase scanning tests for Secure Freight, an initiative by DHS and the Energy Department authorized by the Safe Ports Act enacted last year. The Secure Freight Initiative will deploy nuclear detection devices at six ports: Port Qasim, Pakistan; Puerto Cortes, Honduras; Southampton, United Kingdom, Port Salalah, Oman; the Port of Singapore; and the Gamman Terminal at Port Busan, Korea.

The United States and participating governments are beginning to address policy and operational issues and sign bilateral agreements between countries to go forward with the initiative, said Terry Gibson, director of business development at SAIC’s Security and Transportation Technology business unit. “It’s not all worked out but there’s a lot of very positive activity.”

CBP awarded SAIC a contract in January to install three container inspection systems for the Secure Freight Initiative. SAIC’s Integrated Container Inspection System is used in Hong Kong to scan containers arriving on trucks at port terminals. Gibson said he believes the secure freight program could spawn other scanning initiatives.

Foreign port security isn’t the only maritime concern of U.S. officials. Information sharing is another. DHS and the Defense Department are interested in the concept of maritime domain awareness (MDA) as a means of monitoring seaboard activities The departments’ efforts coalesced in February 2006 an MDA data-sharing community of interest. The group initially focused on tapping information from shipboard broadcast transponder systems that relay information about ship position course and cargo type.

Data-sharing initiatives are getting under way at individual ports, said Roger Hawkes, vice president of National Defense and Domestic Security at Crossflo, a provider of data-sharing software. However, the port environment is complex, often involving city, county or state government authorities or private owners, Hawkes said. A single waterway might have dozens of ports. For example, the 32-mile long Houston Ship Channel has more than 200 separate facilities.

Some larger ports, such as the port of Los Angeles, share information with other ports, and additional projects might begin this year with financial backing from the federal Port Security Grant Program. The program began making funds available for information sharing projects in fiscal 2007, Hawkes said. Grant applications are due in March.

Air Cargo: Pilots under way

DHS has identified two air cargo security threats: explosives devices loaded as cargo on passenger planes and terrorist stowaways seeking to use cargo planes a weapons. The department’s $30 million Air Cargo Explosives Detection Pilot Program targets both scenarios.

The program’s first phase began in June 2006 at San Francisco International Airport to test X-ray and automated explosives detection systems. Air cargo facilities established screening points at the airport.

A second test phase, announced in November, evaluates technologies for detecting stowaways on cargo jets. One device authorities are testing detects elevated levels of carbon dioxide produced during respiration. Seattle/Tacoma International Air Port is the leading test site.

A third test project that will focus on improving existing screening processes will take place at a yet-to-be-identified airport in the Midwest.

All of those air, sea and land pilot tests and programs operate independently, for the most part. Only a few efforts span multiple modes of transportation. For example, CBP’s Customs/Trade Partnership Against Terrorism is a comprehensive program to secure all modes of transportation. But generally, multimodal security efforts are just getting under way.

Paul Fleischmann, security practice principal at Hewlett-Packard Consulting and Integration, said the purpose of multimodal security programs is to verify security at each handoff along the transportation pipeline. “It’s not a smooth transition yet,” he said.

NEXT STORY: ODNI sets guidelines for intelligence reform