A 21st-century approach to democratizing data

The Internet has become a ubiquitous kiosk for posting information. The government’s role in collecting and disseminating data should change accordingly, argue Christopher Lyons and Mark Forman.

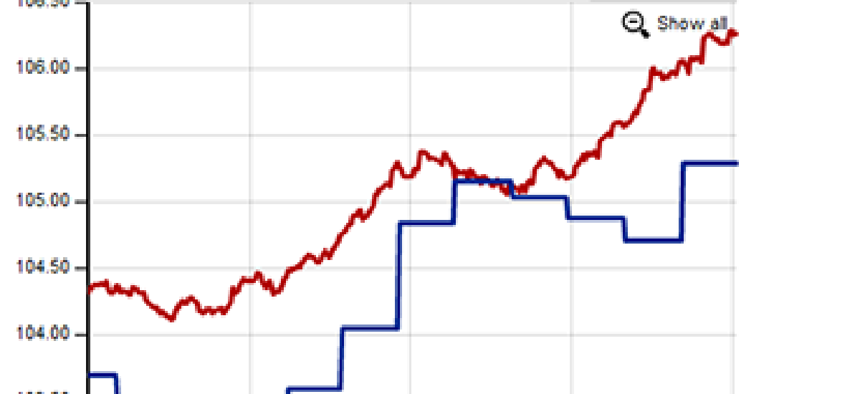

This graph, from MIT's Billion Prices Project, represents a cutting-edge way to gather data and turn it into useful information, according to Christopher J. Lyons and Mark Forman.

“Unbelievable jobs numbers... These Chicago guys will do anything,” Jack Welch tweeted.

Not surprisingly, the recent steep drop in the unemployment rate has given rise to conspiracy comments and discussions about how the rate is derived. Maybe the employment rate is inflated. Maybe it is understated for months. Maybe seasonal adjustments play a part. Maybe.

Recent “democratizing data” concepts hold great promise for improving accountability and even increasing value from the billions of dollars spent on thousands of government data-collection programs. Yet when doubts dominate market-moving, election-shifting data, it is clear that America needs government to change more than how it distributes data. Should government collect the same data and in the same way that it did in the last century? More important, should government’s central role in collecting and disseminating data be changed?

Consider this example: Every day an organization near Boston sends its agents out to collect the prices of thousands of items sold by hundreds of retailers and manufacturers around the world. The agents are dozens of servers using software to scrape prices from websites. In near-real time, the price data is collected, stored, analyzed and sent to some of the largest investment and financial organizations on the planet, including central banks.

This is the Billion Prices Project run by two economics professors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. With a 21st-century approach, two people can collect and analyze the costs of goods and services purchased in economies all over the world using price data readily available online from thousands of retailers. They mimic what consumers do to find prices via Amazon, eBay and Priceline. The Billion Prices Project does not sample. It uses computer strength to generate a daily census of the price of all goods and services. It routinely predicts price movements three months before the government Consumer Price Index (CPI) announces the same.

Beginning in the early 20th century, the Bureau of Labor Statistics responded to the need to determine reasonable cost-of-living adjustments to workers’ wages by publishing a price index tied to goods and services in multiple regions. Over time, government data collections grew through the best methods available in the 20th century — surveys and sampling — and built huge computer databases on a scale only the government could accomplish and afford. Even today, the CPI is based on physically collecting — by taking notes in stores — of the prices for a representative basket of goods and services. The manual approach means the data is not available until weeks after consumers are already feeling the impact.

The federal government’s role as chief data provider has resulted in approximately 75 agencies that collect data using more than 6,000 surveys and regulatory filings. Those data-collection activities annually generate more than 400,000 sets of statistics that are often duplicative, sometimes conflicting and generally published months after collection. The federal government is still investing in being the trusted monopoly provider of statistical data by developing a single portal — Data.gov — to disseminate data it collects using 20th-century approaches.

However, because the value of price data diminishes rapidly with age, it is worth asking why government would invest any taxpayer dollars in finding new ways to publish data that is weeks out of date. More importantly, in an age in which most transactions are accomplished electronically, does it make sense to spread economic data assembled as if we were still in the 20th century?

Old approaches to collecting data no longer invoke a sense of trust. Consider the London Interbank Offered Rate benchmark interest rate, an average of the interest rates paid on interbank loans developed using manual data collection. Those funds move by electronic transactions, but the reporting of interest is an old-school, good-faith manual submission from certain major banks each morning to the British Bankers’ Association. So while the actual transactional data is available instantly in electronic format, it is gathered through individual reporting from each bank daily, creating opportunities for error and manipulation.

The lessons from the Billion Prices Project lie in its 21st-century approach, which affects the breadth, quality, cost and timeliness of data collection. It is an excellent example of how the rise of the Internet as the ubiquitous kiosk for posting information and the unstoppable movement to online transactions require changing government’s 20th-century approach to collecting and disseminating data.

The trusted information provider role of government is ending, and new ways to disseminate long-standing datasets will not change that. Non-government entities are increasingly filling the information quality gap, generating the timely, trusted data and statistics that businesses and policy-makers use — and pay for. The Case-Shiller indices, compiled by Standard and Poor’s using transaction data, are the standard for determining trends in housing prices. The ADP National Employment Report, generated from anonymous payroll information, is widely trusted to accurately relay changes in national employment.

It is time for the government to reconsider its role in data collection and dissemination. The 21st century is characterized by digital commerce that makes large amounts of transactional data available as those transactions occur. Government efforts to collect and analyze data — much like the U.S. Postal Service in the face of texting and e-mail — are becoming more disenfranchised the longer they ignore the paradigm shift.

Statistics developed by independent organizations and companies are already essential to markets, businesses and policy-makers, and the government is increasingly a marginal player. As long as the methods of collection and analysis are open and auditable, government might be better served by shifting away from being a producer to simply being a consumer.

Christopher Lyons is an independent consultant who works primarily with government clients on performance improvement and adoption of commercial best practices. Mark Forman was the government’s first administrator for e-government and IT and is co-founder of Government Transaction Services, a cloud-based company that simplifies and reduces the burden of complying with government rules and regulations.