ABBA, taxes and unintended consequences

Steve Kelman muses on why the Swedish singers dressed so badly -- and what it means for agency rulemakers.

To the occasional amazement or even consternation of friends and family, I am a huge fan of the seventies pop band ABBA. This partly reflects my taste for pop music over genres such as heavy metal or rap, and partly my long-time association with Sweden, ABBA’s home country. (As a sidebar, ABBA aficionados among this blog's readers -- if any -- should listen closely to ABBA songs such as Dancing Queen, where they make the extremely common pronunciation mistake by Swedes of pronouncing the “s” in music to sound like “sick,” because there is no “z” sound in Swedish, or the song Money, Money, where they say “money must be funny,” reflecting the fact that in Swedish the word for “fun” and “funny” are the same.)

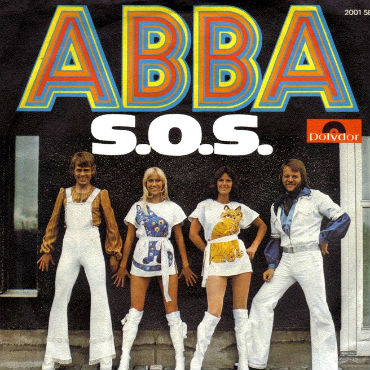

At any rate, I recently saw a bizarre ABBA story reposted on Facebook from the London daily The Guardian, about the loud and mismatched costumes ABBA wore when they performed. The article quotes one of the group members as follows: "In my honest opinion we looked like nuts in those years. Nobody can have been as badly dressed on stage as we were."

It turns out there is a government-related story behind this! Swedish tax law allows work clothing to be tax deductible if it cannot be worn outside the job. In the seventies, the marginal income tax rate in Sweden on high incomes like those of ABBA members was around 80 percent (it is lower today). ABBA apparently deducted their stage outfits with the argument that they would never wear such outrageous stuff off the stage.

This is a funny story, but as a student of organizations and management, I noted a serious issue the story raises -- about how we think about the unintended and effects of rules that are adopted by government. The often-strange consequences can effect both ordinary citizens and those inside government organizations themselves.

The rule that clothing is tax deductible only if it exclusively for work is a sensible one. (I believe the IRS has the same rule.) Or at least it certainly sounds like one, right? The problem is that even rules that are generally sensible often do not make sense in specific circumstances or, as in the case of ABBA’s outfits, can create strange or unproductive behavior distortions.

So how should governments, or organizations, decide when it is appropriate to regulate behavior by rules, and when not? (The alternative is to decide things on a case-by-case basis, and give government officials, managers or frontline employees the authority to make such decisions as needed.)

This is of course one of the classic questions for organizational design -- discussed by organization scholars as far back as Max Weber a hundred years ago -- and I am obviously not going to resolve it in a single blog post. To the extent possible, people thinking about which approach to use should try as best they can to make judgments in advance about how frequently a rule will produce stupid or distorted behavior -- and how important those distortions will be. Rule-makers should also be open to evidence after a rule is developed that stupid or bizarre results are occurring more often than expected.

Rules simplify an organization’s job -- the areas covered by taxation are so many that an IRS that made most decisions on a case-by-case basis would soon have as many employees as the rest of the government. And in situations where corruption is a significant problem, using rules to determine behavior reduces the scope for bribery.

But as the ABBA example indicates, there is also a guffaw factor, which should not be ignored by government. I am guessing that many people who read the ABBA story reacted with, "Here was stupid government at it again, creating bizarre and dysfunctional behavior." Many media stories on the theme of “there they go again, stupid government” involve situations where a rule has stupid consequences in an individual case.

NEXT STORY: Szykman to leave Commerce